First Place Winner

Zambia – School between districts

Design by

Natálie Jendrulková

Jury Critique

An impactful design that redefines the school as both infrastructure and social connector. The bridge concept, integrated with hydroelectric generation and passive cooling, is contextually grounded and technically robust—a resilient model for rural education in Zambia.

-Zhaoxiong Han

Natálie Jendrulková

Natálie Jendrulková is from Třinec, Czech Republic. She recently completed her studies in architecture at the Faculty of Civil Engineering at Brno University of Technology. During her academic journey, she gained practical experience working in smaller architectural studios in her home region and also collaborated remotely on projects related to furniture documentation.

Celebrating Creativity & Vision

Winner’s Spotlight: An Exclusive Interview

Discover the story behind the victory — from concept to creation.

Please introduce yourself and briefly describe your background in architecture or design.

My name is Natálie Jendrulková and I come from Třinec, Czech Republic. This year, I successfully completed my studies in architecture at the Faculty of Civil Engineering at Brno University of Technology.

During my studies, I gained practical experience in smaller architectural studios in my home region, while also collaborating remotely on projects in the field of furniture documentation.

How did you select your rural site, and what role did its geographical and climatic conditions play in shaping your design?

In my final year of studies, I chose a design studio led by Associate Professor Juraj Dulenčín, where we worked on proposals for two schools in Zambia. The inspiration for selecting a specific site came from fellow students who had volunteered in the construction of a secondary school in the village of Kashitu. Thanks to their experience, we gained a deeper understanding of the local conditions and the specific challenges of school construction in the region.

Zambia has recently started covering tuition fees for secondary schools and has invested significantly in education. However, existing schools are often overcrowded or completely absent in remote areas. That’s why we chose a site near the area visited by our classmates—one where a secondary school providing continuity from primary education is currently lacking.

The site lies along a natural barrier—the Mubalashi River—which separates the Mkushi and Kapiri Mposhi districts. This location was selected to make the school accessible on foot to a broad surrounding area with low population density. Its proximity to a main road also ensures access by school bus.

The site’s geographic and climatic conditions strongly influenced the overall concept of the school, which respects the natural barrier and local climate while emphasizing the importance of community connection and access to education.

In what ways does your school design promote sustainability and environmental stewardship within the rural context?

The school design supports sustainability and environmental responsibility primarily by responding sensitively to local conditions and the needs of the rural context. Much of the inspiration was drawn from reference projects, especially the work of Diébédo Francis Kéré. As in his buildings, emphasis was placed on using locally available and environmentally friendly materials—such as adobe bricks, which are inexpensive, easy to produce, and low in embodied energy. The overall construction is designed to minimize the need for external energy sources or artificial cooling.

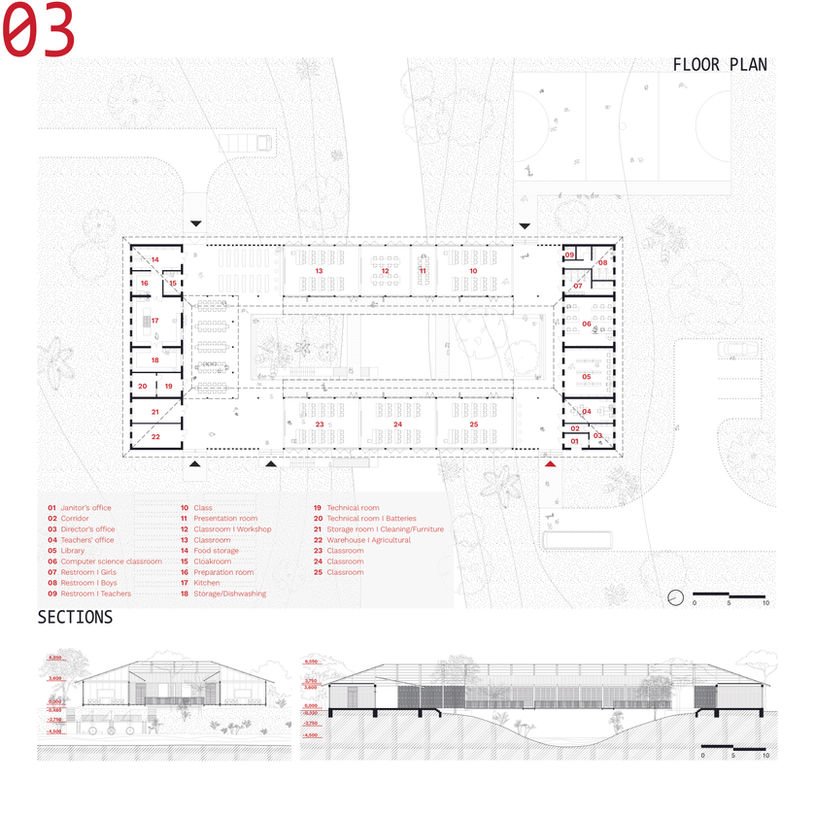

Thanks to the orientation of the buildings and the open central atrium, natural ventilation and shading are ensured, reducing overheating and increasing user comfort. The school is also energy self-sufficient—powered by solar panels and a small hydropower unit, which also enables water to be pumped from the nearby river. The school grounds include a community garden that supports local food self-sufficiency while serving as an educational space.

An important element of the design is the connection between two districts, which the school symbolically and physically links. It is located right on their boundary, near the river, and provides access to education for children on both sides. The project understands architecture not only as building design, but as a tool for social and environmental transformation.

How did you integrate local culture, materials, or traditions into your architectural concept?

The aim was to design a building that not only performs well in the local climate and environment, but also naturally fits into the local context—physically, culturally, and symbolically.

The design was based on thorough research of traditional Zambian architecture, while also considering the current state of rural construction, which is often focused on functionality and simplicity, using readily available materials.

The proposal primarily uses sun-dried mud bricks mixed with cement, which are common and accessible in the local context. Window and door infills, as well as some partitions, are made of wood, allowing for easier assembly and maintenance. The structural system is composed of reinforced concrete and steel elements that ensure the building’s stability and safety.

In accordance with local customs, school compounds are typically enclosed and fenced, which is important for security. This principle is reflected in our design as well—the school is conceived as a safe and protected space, while still forming a main articulated atrium that encourages community life.

What challenges did you face while balancing functionality, sustainability, and contextual integration—and how did you overcome them?

In designing the school, I perceived functionality, sustainability, and contextual integration as interconnected vessels—not as separate categories, but as interrelated components that influence one another.

Throughout the design process, I asked myself many important questions: Would the hydropower plant or the proximity of the river be too noisy or distracting for learning? How high could the water level of the Mubalashi River rise during the rainy season? And is it possible to safely establish a well in the area that would provide a sufficient water supply?

I believe that the real challenges would arise in practice—during a site visit, consultations with local experts, or the actual construction process. Within the scope of the design, however, I worked with the available information and focused more on exploring the idea of a possible solution.

How do your outdoor learning spaces enhance the educational experience in a rural setting?

I believe it goes without saying that the presence of water has a positive effect on people. In Zambia, rivers often create specific microclimates and support lush vegetation, which provides a pleasant, shaded, and cooler environment—ideal for outdoor activities and learning.

Placing classrooms on a bridge-like structure directly above the river offers students an entirely new and inspiring perspective. The combination of nature, elevation, flowing water, and greenery creates a unique space that enhances focus, curiosity, and a connection to the surrounding environment.

Outdoor learning spaces are not only functional, but they also enrich the everyday school experience by bringing students into direct contact with the landscape, water, and natural light.

What sustainable systems (e.g., rainwater harvesting, energy generation, waste management) did you include, and how are they adapted to your site?

A key goal of the design was to ensure a sustainable and reliable supply of energy and water, which is a major challenge in the rural areas of Zambia. Many places lack access to the public power grid, and where electricity is available, it is often unreliable due to dependence on hydropower plants that may fluctuate as a result of droughts caused by climate change.

For this reason, I proposed a combination of two renewable energy sources: photovoltaic panels installed on the school’s roof to meet energy needs during dry seasons, and a small hydropower unit that utilizes energy from the nearby river during the rainy season. This combination provides stable energy self-sufficiency for the school, even in remote areas without dependable infrastructure.

As for water, the design includes a well, rainwater harvesting systems, and the ability to draw water directly from the river to ensure supply even during dry periods.

Overall, all of these systems are tailored to the site’s specific geographic and climatic conditions, allowing the school to operate reliably, sustainably, and independently.

What impact do you hope your design will have on rural education and community life, if it were to be realized in the real world?

Honestly, I believe that the greatest impact would come from the construction of a secondary school itself. In terms of my specific design, it would enable equal access to education for children from both districts, which are currently separated by natural terrain and a river. Thanks to the bridge-like structure integrated into the school, the distance to school would be shortened and safety along the route would be improved—something that is often crucial for children in rural areas.

With its sustainable operation, independence from the central power grid, and access to water, the school can function reliably even during periods of drought or infrastructure outages, enhancing its long-term resilience.

Overall, the school could not only support education, but also strengthen the economic and social resilience of the rural community and offer a new impulse for the development of the surrounding area.

Share this design journey

Spread inspiration and connect with innovative design perspectives