Second Place Winner

U-Ebu Apartments

Design by

Melanie Rizzo & Janelyn Romero

Jury Critique

"The design captures the spider’s precision to create a suspended living environment of balance and light."

-Amal AjithKumar

Melanie Rizzo & Janelyn Romero

Melanie Rizzo is a Master of Architecture student at Florida International University whose work explores the integration of biomimicry, sustainable design, and urban resilience. With a foundation in Communication Arts and Media Design, she approaches architecture as both a technical and cultural dialogue, where environmental systems, finance, and community engagement intersect.

Professionally, Melanie serves as a Program Manager with Project Destined, where she mentors university students in real estate fundamentals, investment strategy, and market research. Her previous experience as a CAD Drafter at Dade-Made Fabrication has given her hands-on expertise in steel design and fabrication, strengthening her ability to translate design concepts into buildable solutions.

Drawing from her combined background in architecture, finance, and fabrication, Melanie’s work seeks to bridge innovation and feasibility, developing design approaches inspired by nature that are grounded in economic and environmental awareness.

Janelyn Romero is currently pursuing a Master’s in Architecture and holds a Bachelor’s degree in Anthropology with minors in Digital Media and Architecture, along with a Real Estate License. As President of the American Institute of Architecture Students (AIAS), she actively fosters collaboration, leadership, and a sense of community within the academic environment.

With a strong foundation in real estate and business, Janelyn Romero brings a unique ability to build meaningful relationships and understand the expectations people have of the spaces they inhabit. Hands-on experience with both residential and commercial properties has provided valuable insight into how design intersects with functionality and human experience.

Her architectural focus centers on reimagining spaces to bring communities together, celebrate cultural identity, and promote sustainability. Through thoughtful design, Janelyn Romero seeks to transform environments once seen as unusual, unusable, or without purpose into meaningful spaces that inspire connection and reshape perception.

Celebrating Creativity & Vision

Winner’s Spotlight: An Exclusive Interview

Discover the story behind the victory — from concept to creation.

1. Inspiration and Concept

What specific insect colony or natural phenomenon inspired your design, and what aspects of it did you find most fascinating or influential?

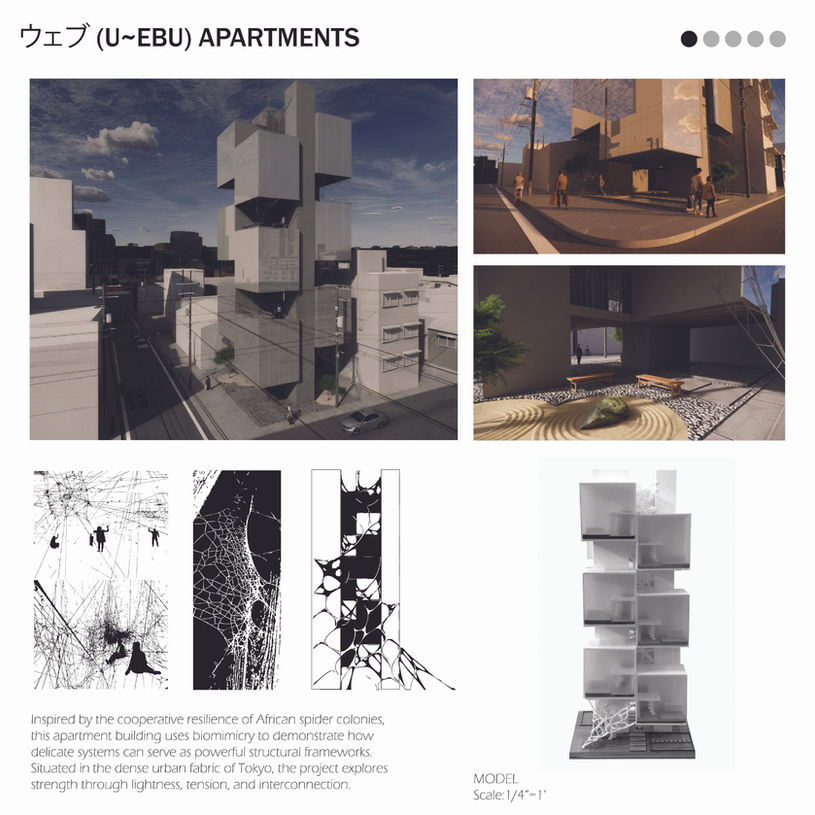

Our design was inspired by African spider colonies. This specific type of spider was interesting because spiders are usually solitary creatures, yet these spiders live together. The appeal of their intricate merged webs was fascinating; they were complex and three-dimensional. The aspect that drew us in deeper was the idea of a spider community within their webs.

Through research, we found that different parts of the web had different functions. How fascinating is it that these small insects have found a way to survive together and create organized spaces within their webs. They managed to create a home anchored in different places but defined by negative space come to life through a physical aspect of a web separating use in different parts. One area designated for food to be trapped and saved, another to capture water, and an area for shelter. All connected by what we define as a series of corridors used by the spiders in this colony.

2. Translation from Nature to Architecture

How did you interpret and translate the structural or social principles of insect colonies into your residential design concept?

Analysing such an interesting insect such as a spider takes physical observation and testing. To create our residential design, we went through a series of testing to determine the delicate structure of a web. We created a few bug models testing architectural elements with spiderweb qualities. I, Janelyn, felt like I needed to understand how we could translate a web into a plan by creating my own web using pipe cleaners. The practice of creating this web helped me understand that hierarchy and suspension should be a part of the plans. The ideas came very clearly to us from that moment. To step into structure a bit deeper, I, Melanie, created a structural test model and ran it through fusion 360. Through a series of tests, I was able to determine where the most structure would need translating into two central cores of stairs and the other an elevator. The results of these structural tests also gave us the idea of encapsulating central core with webbing for a subtle experience to our users.

3. Design Process

Could you walk us through your design process — from research and concept development to the final presentation?

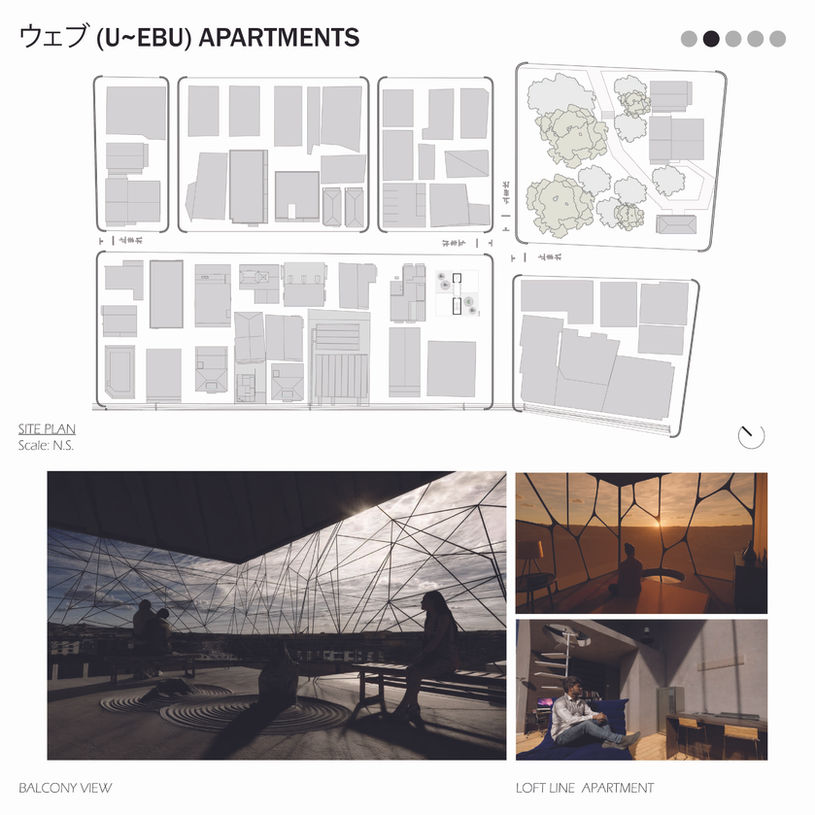

The design process for our structure was challenging. We dove into lots of research for different kinds of spiders before choosing the African Spider as our subject. Through a series of conversations determining what we wanted to explore in our design based on our information on spiders. Observation of spiders creating webs in time-lapse videos and pulling ideas from how they created their homes. We moved to a series of bug models exploring our personal ideas on elements that reference a spider. Each of us focusing on different parts of web structure, I, Janelyn, focused on the creation and movement of the spider in its web. Melanie focused on creating a structurally sound core through a variety of tests in fusion 360, where she found the need for suspension would need to be supported greatly through a central core and a variety of supported joints. The plans flowed quickly after our research and test stage, we knew we needed to incorporate hierarchy on our plans through the use of elevated floors throughout the residences. Entry, Kitchen, and Restrooms would be on our lowest floor. The library/office/nook area would be on the second highest floor. The living room would be in the highest part of the floor to separate function and allow focus on the beautiful exterior city views. An entire space divided by hierarchy to illustrate a beautiful flow of function much like the spacing of the webs of a spider. The loft-line residence created more reference to suspension through a simple flow from the second highest floor to a spiral staircase which leads its user to their bedroom. A reference to where a spider usually remains within its home, defining its centre, and suspended by its surrounding web. The gardens and communal floors came last; we wanted to create a seamless flow between the location of our site, the city’s culture, and approach communal spaces much like African Spiders would. This concept took many tries before it took form into simplistic gardens with rocks, sand, and foliage.

Our final presentation needed to reflect our process and our final product. We took our time carefully considering how we would organize our presentation. We decided to introduce our project with city views, a view into our model, and introduction to our concept of spiders through diagrams. Each diagram referenced something different. One was an exploration of the human interacting with a web, the other was an exploration of a spider and its choice of anchors for its home, and lastly our cores interacting with a web. We followed this with a site map to reference our ground floor garden referencing the nearby shrine. The rendered views referencing the map to the area and what a resident may see in the communal and private spaces. Next, we followed with the plans of both types of residences to show layout and floor hierarchy. Along with a diagram of our vaulted loft structural placement and a reference to the need of central cores for our residences. Lastly, we explored demonstrating experience by incorporating elevations, section perspectives, and room perspectives. By introducing perspectives, our intention was to show suspension and hierarchy within the spaces like the Tatsumi Apartment House (Hiroyuki Ito Architects) room perspectives and section drawings.

4. Sustainability and Environmental Response

Insects build habitats that are naturally adaptive and sustainable. How did your design incorporate these environmental strategies or ecological principles?

U-Ebu was created with many factors of adaptability and sustainability. We proposed to create a public space in our site that would be used by the community and its residents. The ground floor garden needed to be created in a way that would adapt and fit in its environment. Keeping this in mind we decided to incorporate some elements of a nearby shrine in our site. Incorporating trees and stone as a place of reflection and breaking up the city scape by referencing nature. Our lofts and studios were created as a precast element. Each box of 20ft x20 ft x20 ft, would be assembled and simply placed on our cores through use of suspended wires, steel connections, and welded joints. To diminish our footprint, instead of adding more residents we decided to create community spaces on every floor, areas that could be used as a place of reflection or a placed to enjoy with your neighbours. Lastly, because concrete has temperature control capabilities, we created every box with 5 main components of concrete and 2 sides made of mirrored glass. Both materials which are known for its ability to control temperature. Concrete absorbs heat and protects during the cold, and the mirrored glass reflects solar heat from its interior, reduces glare, and gives a sense of privacy.

5. Spatial and Structural Innovation

What innovative spatial or structural solutions did you derive from studying insect-built habitats, and how do they enhance functionality in human living spaces?

One of the most relevant solutions we found exploring spiders was the use of natural elements. Humans only need four elements to survive like spiders: shelter, air, food, and water. Spiders use their spiderwebs as the centre of their lives. Organized spaces which encapsulate light, capture water, direct water, circulate wind, and capture food.

The idea that spiders have an organizational structure influenced the idea of using hierarchy to separate function.

Within the spiderweb, there are a variety of different sized gaps. Smaller gaps allow the spider to trap food and wrap them for later. Medium gaps carry enough space to trickle water down. Water rarely reaches a spider’s core instead stay within the middle and outer parts of the web. Large gaps allow for wind circulation, (have you noticed how sturdy a web is when faced with wind?) the maximum amount of airflow to maintain the webs stability.

We feel today’s architecture forgets to incorporate elements that create function, instead we should take the simple survival ideas of a spider and incorporate it into our ideas. Defining space differently by manipulating the area subtlety not so much using walls to separate space but using elements like hierarchy and suspension to define space and giving it function.

6. Community and Social Organization

Insects thrive through cooperation and well-defined social structures. How did these ideas influence the way you approached community or shared spaces in your project?

African spiders are unique because they are one of the few that live in colonies. To determine how this specific community of spiders works we took a deep dive. The reference of function was apparent. This colony had specific areas for food, water, and shelter connected by what looked like corridors. We took this idea and incorporated it within our apartment layouts but referenced how these spiders took shelter together as our driving force for communal spaces. The shared spaces needed to be open but connected. They also needed to be mirrored like the spiders in the web facing each other. Through this acknowledgement, we created our shared spaces to have a natural flow from the corridor. The idea of having structural webbing as our railing not only encapsulates the idea of web but was a system to allow for maximum cross ventilation and light penetration. Simple gardens in these spaces felt appropriate to allow for reflection and communal interactions.

7. Challenges and Learnings

What were the biggest challenges you faced in translating biological inspiration into architectural design, and what did you learn through this process?

Our biggest obstacle was translating the lightness and transparency of a spider’s home. How could we encapsulate a human in a web figuratively before incorporating the literal? The challenge began in form, a spiderweb is either shaped like a funnel, 2d, or anchored in many points. We experimented with organic forms at first. Modelling webs and then placing planes and linear element. It was a long process of trial and error, until one day as we showed each other our ideas, Melanie came with a model of intersecting boxes touching at the edge. From that moment we experimented with that shape until we found our core elements. It became apparent that a web can look the same but inverted from another side, which influenced us to create the same intersecting boxes mirrored over the core to create our final form. Once the final form was created, the idea of lofts came naturally.

8. Future Vision

How do you see biomimicry — especially insect-inspired design — influencing the future of sustainable residential architecture?

Biomimicry is a missing element from conceptual design process. Why? What better precedent than to look at the creatures who have survived through the increased change the world has gone through. Insects have found ways to adapt to their changing environments and maintaining their connection with nature. Humans are no different in adapting to their surroundings but lack the knowledge to experiment further with nature as part of their living experience within their homes. A home is not just 6 walls with other walls separating space. A home is a space with the maximum amount of function for the humans who dwell in it. We feel that the next move for residential design is using insects as a method to determine layout and define function.

We can draw inspiration from all kinds of nature and implement the movement that benefits our lives. Mechanisms that have stood and adapted against the trial of time and have managed to survive. Many of our layout and structural questions have already been answered, we just need to be open to looking and observing nature as a means of our response.

Share this design journey

Spread inspiration and connect with innovative design perspectives